Conference:

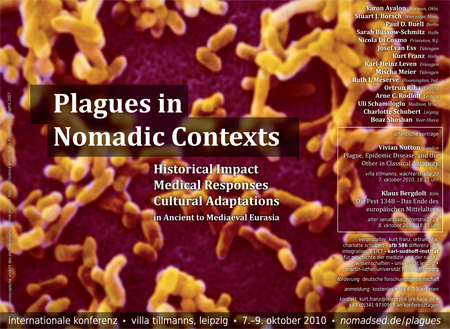

Plagues in Nomadic Contexts:

Historical Impact

Medical Responses

Cultural Adaptations

in Ancient to Mediaeval Eurasia

7.-9.10.2010

![]() Conference Report

Conference Report![]() Programme & Abstracts

Programme & Abstracts![]() Poster

Poster

International Conference organized by SFB 586 (B1, E7) and the Karl-Sudhoff-Institut für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften, Leipzig

Venue: Villa Tillmanns, Wächterstraße 30, Leipzig

Date: 7-9 October 2010

Convenors: Kurt Franz, Ortrun Riha, Charlotte Schubert

Contact: kurt.franz@orientphil.uni-halle.de

Until now, plague and pestilence have almost exclusively been examined in relation to settled societies and agrarian economies. However, the interaction of nomadic and sedentary elements has made society and culture function in particular ways, and, it must be presumed, health and disease do not represent exceptions to this. This conference raises the question of how and to what extent epidemics have affected societies that have experienced nomadic forms of life, and whether, furthermore, the presence of nomads have influenced the impact of epidemics.

As a working hypothesis it is assumed that epidemics, and human responses to them, have developed differently in societies in which nomads have had a distinct role. Historically this may pertain, for example, to the spread of the epidemic, its effect on land usage, tenure and taxation, medical and administrative counter measures, markets and power relations.

Furthermore, coeval attempts at giving meaning to epidemics deserve discussion, especially as ideas regarding contagion and myasmata, God's punishment etc., were often linked to perceptions of steppe/desert living and to the nomad as a conceived figure. For example, medieval Muslim authors presumed that a harsh steppe environment hampered the intrusion of the plague. With these presumptions such authors also elaborated upon culturally encoded notions of wilderness and purity, hardship and the resolute nature of the nomad. Essentially the explanation of epidemics and their handling has often remained culturally specific. Illustrating how nomads have been included therein, in reference to otherness and role assignments, should offer common ground upon which to discuss various phenomena.

Therefore, the conference aims towards the exploration of a possible new interface connecting the study of history, culture, and the history of medicine. In order to allow for a comparative perspective, the conference will bring speakers with a background in Epidemiology, Classical Antiquity, Byzantium, the Islamic Middle East and Iran, Imperial China and Latin Europe together. This implies a very broad understanding of nomadic practises, including post-nomadic life and reference to mobility in general. Equal attention will be paid to literary and symbolic representations, be it self conceived evidence of nomadism or external documentation. Topics will cent

- Modes and paths of infection, demography, spaces and environments

- Source criticism and terminology

- Endeavours of healers and physicians, and expectations upon them

- People's reactions and the religious/scientific discourse

- Order and disorder, defence and innovation

The conference will be co-hosted by the Karl Sudhoff Institute for the History of Medicine and Science, University of Leipzig. As the institute is the century old birthplace of the History of Medicine as a distinct discipline and has been a renowned research institution ever since, Leipzig is, indeed, the perfect city for the introduction of nomadic contexts

The official languages will be German and English.

The exchange on plagues in nomadic contexts will be one part of a twin conference. It commences on 4 October at the same venue with the discussion of “Disaster and Relief Management in Ancient Israel, Egypt and the Near East”.

Programme

October 7th, 2010

Leipzig, Villa Tillmanns, Wächerstr. 30

| Opening |

17:30 | reception and registration |

18:15 | welcome address |

18:25 | greetings |

18:35 | opening lecture |

October 8th, 2010

Leipzig, Villa Tillmanns, Wächterstr. 30

09:00 | introductory remarks |

| 1 • Contagion and Spaces chair |

09:15 | Arne C. Rodloff (Leipzig): |

10:00 | Ruth I. Meserve (Bloomington, Ind.): |

10:45 | break |

11:15 | Kurt Franz (Halle): |

12:00 | Yaron Ayalon (Norman, Okla.): |

12:45 | lunch at Café Kowalski |

| 2 • explanations and imaginations chair |

14:30 | Charlotte Schubert (Leipzig): |

15:15 | Mischa Meier (Tübingen): |

16:00 | break |

16:30 | Karl-Heinz Leven (Erlangen): |

17:45 | joint departure |

18:15 | Public lecture Klaus Bergdolt (Cologne): |

October 9th, 2010

Leipzig, Villa Tillmanns, Wächterstr. 30

| 3 • Livelihoods and Mobility chair |

09:00 | Stuart J. Borsch (Worcester, Mass.): |

09:45 | Ortrun Riha (Leipzig): |

10:30 | break |

11:00 | Sarah Büssow-Schmitz (Halle): |

11:45 | Boaz Shoshan (Beer-Sheva): |

12:30 | lunch at Mio Restaurante |

| 4 • Treatment and Transformation chair |

14:00 | Paul D. Buell (Berlin): |

14:45 | Uli Schamiloglu (Madison, Wisc.): |

15:30 | break |

| discussion |

16:00 | general response |

16:15 | general response |

16:30 | discussion |

ca. 17:30 | concluding address |

October 10th, 2010

Leipzig

| Optional Excursion |

10:00 | guided city walking tour |

CONTRIBUTIONS

Yaron Ayalon, Norman, Okl.:

When Nomads Meet Urbanites: The Outskirts of Ottoman Cities as a Venue for the Spread of Epidemic Diseases

Historians often understand epidemics – breaking out in densely populated areas and facilitated by poor hygienic conditions – as an urban phenomenon. Although diseases surely affected nomads, we know very little of the effect such calamities had on people’s daily lives outside major cities. This is very much apparent in the Ottoman Empire, where we are almost completely in the dark with respect to non‐urbanites, let alone nomads. While the latter left practically no written evidence, we can penetrate their world through looking at the points of contact between them and sedentary populations.

In Ottoman cities, such interactions often happened at the outskirts of cities, where nomads came to trade and offer various services. In times of famines, nomads and villagers were attracted to cities in hope of finding food. When famines coincided with another disaster, such as a flood, fire, or earthquake, many urbanites moved out of the city center and established provisional lodgings in its vicinities, creating a hodgepodge of nomads, villagers, and urbanites sharing very limited space. Since the suburbs also housed businesses that produced the most pollution and noise – tanneries, butcher shops, soap factories – the concentration of so many people there guaranteed worsening hygienic conditions. This eventually led to the outbreak of epidemics, as happened in Aleppo in 1757–62. The question in which direction epidemics spread – from the vicinity into town or vice versa – and the role nomadic populations played in disease transmission, for instance from one city to another, is not entirely clear. In Ottoman and European sources, there is evidence supporting arguments that nomads both disseminated disease agents among urbanites, and suffered due to their temporary settlement around cities. What exactly was the role of nomads in spreading epidemics in the Ottoman Empire is the quandary I will try to resolve in my presentation.

Klaus Bergdolt, Cologne:

Die Pest 1348 – Das Ende des europäischen Mittelalters

The Plague of 1348 – The End of the European Middle Ages

The impact of the plague of 1348 (which stroke, more exactly, the continent between 1347 and 1349) on the European countries was extraordinary. The difficult situation of the authorities, of doctors and theologians was intensified by the fact that comparable epidemics which had devastated many Mediterranean towns and harbours in the 6th and 7th century had been forgotten. So the Black Death (this name was only a later paraphrase) surprised the communities, to quote Petrarch, as an – in the strict sense of the word – “unseen” and “unheard‐of” catastrophe. That its origin was somewhere in Asia – a continent as far away as uncanny – complicated psychologically the situation. Nearly a third of the population died, in the towns not seldom many more. Economics were, as we know from many towns, paralyzed, executive and legislative bodies out of function, families in dissolution. The spreading of the feared epidemic and typical all day conflicts, sometimes already caused by its fama, are presented, also by literary sources. It can be demonstrated that anxiety and mortal fear did not only impair adequate personal and public reactions but favoured, on the other hand, a new concept of subjectivism which was regarded as the beginning of renaissance philosophy.

Stuart J. Borsch, Worcester, Mass.:

Epidemic and Landholding Structure in Egypt and England

Contrasting outcomes in Egypt and England are the focal points of two disparate economies that shared certain common elements. Egypt’s trajectory bent sharply downwards in the wake of epidemics that began in the mid‐fourteenth century. England was better able to withstand the effects of depopulation and its economy was marked by a recovery on a per‐capita level in the fifteenth century. The question here is how this divergence between the two economies became so steep. The evidence suggests that contrasting outcomes were driven by the difference in the structure of the two landholding regimes.

In both economies, the labor pool dropped precipitously. Rural labor became scarce. In both countries, landlords sought to resist any upward pressure on wages and contain any pressure from the peasantry. Varieties of labor, rent, and peasant mobility legislation were introduced in both countries. In England this labor legislation failed. It was slowly eroded by the economic pressure of scarce labor demand in the agrarian sector. Eventually landlords were forced to lower rents and offer flexible tenancies. This process witnessed the end of what was left of the manorial system.

Egypt’s various efforts at collective labor control were unfortunately relatively successful. Legislation on mobility, or more particularly, on rents, worked to produce a countervailing pressure in the agrarian sector of the economy. The peasantry fared badly. This non‐economic solution exerted a strong centrifugal pull that drew agrarian labor away from active participation in the rural sector. The resulting outcome was a sharp decline in the mainstay of Egypt’s economy.

Paul D. Buell, Berlin:

Qubilai and the Rats

Although the medicine of the ancient, Medieval and recent steppe world was necessarily less developed than that of the sedentary domains, including China, this is not to say that there were no medical traditions present there. The nomadic peoples could also be sophisticated in their understanding of disease and its causation. In the present paper, I will look primarily at the example provided by the Mongols, who probably have the longest and best documented history of any steppe group, as well as having a particular position in world history because of the cultural exchanges occasioned by the Mongol empire.

I will begin with an examination of native views of disease and ways of responding to it, including a well developed Mongol sense of avoiding disease, even embracing serious ones such as bubonic plague, which is endemic to Mongolia, in the first place. This will include a survey of Mongol use of materia medica, starting with the earliest evidence for this in the Secret History of the Mongols, but also an examination of Mongolia’s powerful shamanic tradition, which will be compared to traditions found among other steppe Altaic groups in the area, particularly but not exclusively the Kazakhs.

Finally, I will look at how the Mongols responded to their own health issues and the health issues of a larger society around them by appropriating other people’s systems, this included Arabic medicine, Chinese medicine, and most important, Tibetan medicine. A focus of the discussion will be how the Mongols managed to combine all of these traditions to produce their own classical medical system which, although considered Tibetan, actually has a more mixed pedigree. In passing, I will touch on the key issue of how the Mongols managed to be associated with the spread of bubonic plague without suffering from it that much themselves. Was this cross‐immunity or a clear strategy of plague avoidance, and what are the implications of this for the larger study of history and of medicine.

Sarah Büssow-Schmitz, Halle:

“The Disease Killed the One Who Stayed as Well as the One Who Moved:” Plague and Mobility in Mamluk Chronicles

The plague traversed the whole known world within only a few years. Contemporary Arabic authors describe the feeling of how a death‐bringing disease was approaching and could not be stopped as particularly terrifying. In this vein, a later chronicler personified the disease as a “creeping snake,” and representatives of the miasma theory supposed that it was a wind that carried the plague from one land to another. The question arose as to whether one could protect oneself from the disease by moving location, for example by escaping into a non‐affected region. Many scholars, especially religious authorities, objected to this kind of reaction, arguing that the plague was not contagious but that it was sent by God, which made any attempt to flee it a vain endeavour. However, some physicians such as the Andalusian Ibn al‐Khatib (1313–1374) made a strong case for the position that the plague was contagious and that one could theoretically avoid it. In this context they also assumed that there existed a connection between health and different types of space. The densely built‐up city with its unhygienic conditions was contrasted with the habitat of desert and steppe dwellers which was believed to be healthier.

But what do we know about practical and literary answers to the plague beyond the medical discourse? In how far did mobility play a role there? The paper will discuss three accounts on the Black Death 1347–1349 by Mamluk chroniclers. It will be argued that the chronicles display more complex connections between plague and mobility than in medical treatises. Although the debate on the (im‐)possibility of escape also plays a role here, several reactions to the disease are described that involved moving. Two topics will be discussed: mobility as metaphor for characterising the Black Death and strategies and practices of defence against the plague which involved physical mobility or the limitation thereof, such as processions and the closure of markets.

Nicola Di Cosmo, Princeton, N.J.

discussant

Josef van Ess, Tübingen

discussant

Kurt Franz, Halle:

Well off in the Wilderness? Muslim Appraisals of Bedouin Life at Times of Plague

The general difficulty of monotheisms in reconciling human despair regarding the horrors of epidemics with belief in divine justice was intersected in the Middle East by a fairly specific condition. Almost every aspect of human life revealed itself differently in the steppe/desert areas, in which nomadism was the prevalent mode of life, in contrast with the urban/rural areas characterised by sedentariness. Against the constant ecological background of vast wastelands that fringed and even separated the comparatively small‐sized arable tracts of land, the coexistence of Bedouin and settled populations has been inscribed in the region’s culture from early on. I shall argue that this interrelation and its perceptions recur in mediaeval Islamic concepts of epidemic.

These concepts were far from unanimous. One was based upon a pious tradition stating that there is no contagion; its advocates, rather, stressed divine will and stipulated immobility during epidemics. The other opinion, or strand of opinions, recognized the possibility of contagion, and it enquired into the impact of natural environments on the spread of disease, following ancient medical learning. Along with this went assumptions that wilderness itself was endowed with salubrious air and other properties that prevent miasmata, thus forming a barrier to contagion. This medical geography in nuce combined well with the notion that the hardness of life there was healthy and rewarded the Bedouins with robustness. Times of plague, it seems, reveal the superior resistance of Bedouins against infection and make their life appear advantageous.

I will review these appraisals with regard to pre‐Ottoman periods. How do the number, geography and magnitude of pestilential epidemics that reportedly spread into steppe/desert areas compare to those that did not? Is there evidence to suggest that disease and mortality struck the Bedouins less than peasants and townspeople? How shall we, therefore, judge the consistency of each concept between factual occurrences of plague and cultural encoding – and did the Black Death of 748–749 / 1347–1349 induce a change in concepts?

Karl-Heinz Leven, Erlangen:

Die Tollwut der Barbaren: Über wahre und falsche Ursachen von Seuchen bei byzantinischen Geschichtsschreibern

Barbarian Rabies: True and False Cause of Epidemics as Seen by Byzantine Historians

In the year 554 a Franconian military troop in Italy under the command of Leutharis, according to the Byzantine historical writer Agathias of Myrina (Hist. 2, 3, 4 ff.), was met with a “Plague” (νόσος τις λοιμώδης). The causes of this sickness, which showed with Leutharis himself as an especially repugnant, “Rabies” type illness, were numerous: dietary mistakes, the unclean state of the air and such reasons, typical of contemporaneous medicine, were named. To this the “true” cause of the sinful and wanton behaviour of the Barbarians was added. The characteristic mix of causes of sickness, as seen in this episode of Agatha, is to be seen in the wider context of Byzantine depiction of disease. It shows that medical concepts and theological explanation structures, dependent on literary origins, were adapted. Here the process of “imitation” (μίμησις) plays a decisive role, as classically understood literary models, with their own tradition of disease depictions, reappear.

In relation to content it is also interesting that the “plague” in Byzantine literature appears in two forms. As in the example of Agathias it comes into view as a disease of warmongering soldiers – within these ranks the carriers of the sickness wander. The other form, the most common, sees the disease actually moving itself: like a conscience ridden tax collector, so Procopius of Caesarea, the disease meandered through the mainland and islands of the empire, taking its tribute in death. This personification and demonisation of the threat of plague stabilised itself as the dominant explanation structure, within which medical factors only constituted one layer.

Mischa Meier, Tübingen:

Die “Justinianische Pest”: Mentalitätengeschichtliche Auswirkungen einer Pandemie

The “Justinianic Plague”: The Impact of a Pandemic on Mentalities

In the years 541/542 a deadly epidemic pervaded the entire Mediterranean region for the first time ever. It resulted in an unimaginable number of victims, especially in large urban centres such as Constantinople but also in rural areas. Not only the immense physical and material consequences of this “Justinian” plague permeated various spheres, but the experience of mass death at an, until then, unprecedented level was also of great effect. This has only been taken seriously within academic discourse during the past few years and has been incorporated into the discussion complex regarding the end of antiquity. The planned paper will provide an overview of these events and the contemporary discussion regarding them.

Ruth I. Meserve, Bloomington, Ind.:

Traditional Disease Boundaries and Nomadic Space in Central Eurasia: The Search for Order

The entire field of Central Eurasian studies and various types of nomadism functioning within the region are undergoing modernization and vital change. Yet disease and medical history remain absent from many of these discussions. To begin to remedy this situation, disease boundaries in traditional nomadic societies of the region are examined. Very quickly, one recognizes that these boundaries occupy different perspectives, reflected in the local religious, economic, social and political life of the community. Sometimes carefully expressed in folk terms, language played a key role in addressing disease. Nomadic populations were intimately concerned with both human and livestock conditions, especially as deaths mounted during epidemics. As a result, a number of patterns in nomadic space emerged as responses to disease outbreaks. Preliminary pattern concepts with examples are offered.

Boundaries may be visible or invisible; concern for ancestors and fu‐ ture progeny exist; disease “maps” explain causes and routes of transmission. Both physical and metaphysical, these boundaries provide concepts of early transmission and “contagion” as well as treatment and “quarantine” within nomadic societies. Some of the diseases mentioned will include leprosy, tuberculosis, anthrax, smallpox, plague and foot‐and‐mouth disease. Materials are drawn from traditional medical texts, palaeopathology and archaeology, ethnography and anthropology, as well as the sciences (biology, geology, etc.). In many ways it will take the work of experts from many different disciplines to reconstruct the medical history of nomadic Central Eurasia.

Vivian Nutton, London:

Plague, Epidemic Disease, and the Other in Classical Antiquity

Greek and Roman explanations for epidemic disease, which might include what today is known as bubonic plague, differed substantially from those for individual illness. While they often included some reference to the individual nature of plague sufferers, they also ranged much wider in their search for “causes.” Divine anger was far more frequently mentioned as an explanation for an epidemic than for an individual disease, and the most common assumption, bad air or miasma, was loaded with a variety of non‐medical correlations. Often too, there was an element of “the other” involved, sometimes in ascribing the onset of an epidemic to something coming from “over there,” sometimes in blaming the outbreak on association with things foreign. The expansion of the Greek, and later the Roman, world also brought new interpretations, including demonology, and new explanations such as the notion of touch or contagion. This paper will look at this development from Homer and the Old Testament down to the 6th and 7th century.

Ortrun Riha, Leipzig:

Flieh weit und fern: Medizinische Empfehlungen in mittelalterlichen Pesttraktaten

Cito, longe, tarde – Medical Recommendations in Medieval Plague Treatises

Considering the helplessness in the face of Black Death, the variety of medical treatises is remarkable. In fact, the catastrophe induced new sorts of texts and inspired physicians to strike new paths, if only on traditional ground. Old concepts were adjusted to the demanding task, and the needs of the frightened public were met in a satisfying way. Plague treatises rank among the texts most widely read by a lay public and early came to the letterpress. This is surprising, since from our point of view, the content is trivial and not helpful. Nevertheless, the texts evoked a feeling of security and made people believe to be in control of their destiny. At the end, it was not medicine that met the challenge: in the case of an epidemic, public health policy is called for.

Arne C. Rodloff, Leipzig:

Mikrobiologische, epidemiologische und immunologische Grundlagen der Pest

Microbiological, Epidemiological and Immunulogical Foundations of Plague

Charlotte Schubert, Leipzig:

Griechen, Nomaden und Seuchen: Eine verlorene Spur?

Greeks, Nomads and Epidemics: A Lost Trace?

The ancient nomad image is a narrative pattern, which, in its structure, is based upon the dichotomy of settled and nomadic peoples. Behind it lies the assumption that human life forms are basically bipolar, either nomadic or settled. Various representational practises, as well as the interchanging between reality and the “social construction of reality” mark the history of the construction of this dichotomy in antiquity. Ancient descriptions of epidemics do not allow for a correlation with nomads; at least there exists no explicit depiction of this type in antique literature. Yet using the example of the communication of one of the most famous epidemic cases in antiquity, the so‐called plague at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War (430 B.C.), it can be shown that the image of the nomad had anchored itself within the canon of Greek self representation.

Uli Schamiloglu, Madison, Wisc.:

The Black Death and the Transformation in the Nomadic‐Sedentary Relationship in Western Eurasia in the 13th–16th Centuries

The arrival of the Black Death in the mid‐14th century had profound consequences for the inhabitants of Western Eurasia. While there are extensive reports in the chronicles for the neighboring regions inhabited by Slavic populations, the written records describing events in the Golden Horde itself are far more limited in scope. Nevertheless, if one considers the full range of consequences of the Black Death, there emerges a picture of profound upheaval in political, social, economic, cultural, and religious life in Western Eurasia.

This paper focuses on certain ethno‐linguistic and demographic transformations. The evidence points to the collapse of the Golden Horde as a state and a decline in the newly‐established urban centers. One can also argue for a decline in the traditional sedentary populations of the Middle Volga region, including the decline or disappearance of traditional ethno‐linguistic communities. In traditional sedentary regions the political vacuum left by the collapse of centralized states was filled by the much smaller khanates of the “Later Golden Horde” period (15th–16th/18th centuries). In the nomadic regions, beginning in the second half of the 14th century, one sees a rise in the size and influence of the nomadic component, which in Western Eurasia meant the Kipchak Turkic nomads. With the collapse of the Golden Horde as a centralized state we see the sudden rise in nomadic confederations such as the Great Horde, the Özbeks (Shibanids), the Nogay Horde, and the Kazakh Hordes.

This paper argues that the nomadic populations of Western Eurasia did not suffer the same demographic decline from bubonic plague as the sedentary populations. For this reason, they became politically more significant relative to sedentary states such as the Khanate of Kazan, which no doubt continued to suffer from waves of plague through the 15th century. It also argues that this phenomenon underlies the ethno‐linguistic Kipchakization of sedentary regions throughout Western Eurasia beginning in the late 14th–early 15th centuries.

Boaz Shoshan, Beer-Sheva:

Fellahin and Bedouin: The Aftermath of the Black Death in Egypt

The plague cycles that ensued in the mid 14th century rendered precarious the sedentary structure confronting Bedouin population in Egyptian lands. Drastically reduced agricultural labor was unable to sustain irrigation systems and a significant result was a stream of peasant migration. Rural depopulation coincided with an increasing Bedouin pressure, the penetration of pastoralists and the increase of wasteland, especially in Upper Egypt. In the 1380s, as the Mamluk sultanate was no longer able to maintain sufficient forces to impose its authority, a group of Hawwara Berbers was installed in the Asyut region to counter Bedouins.

Elsewhere in Egypt the fragile rural‐pastoral balance was also under stress. In the last decades of the 15th century a large number of expeditions were directed against the Bedouins in Lower Egypt. In 872/1468 Ibn Taghri Birdi stated that never have Bedouin ravages intensified as in these days and they infested the lower provinces. His general statement that the Bedouins confiscated iqtas in the Buhayra coincides with early Ottoman land registers revealing the significant migration of peasants and the loss of about 20 per cent of iqtas to Bedouin hands.

This process of so‐called bedouinization has to be fine‐tuned, however, in the light of Nicolas Michel's important research of the Ottoman archival material. It reveals that about 1528 Bedouin shaykhs in the Buhayra were involved in positive initiatives toward land reclamation. The Qanunname of 1525 assigns to Bedouin shaykhs a status equal to that of provincial inspectors. These recently discovered data point out an intriguing picture where collective Bedouin ravages can be juxtaposed to individual, financially motivated investments in agriculture.

Conference Report

by Kurt Franz and Ortrun Riha

Published in:

H-Soz-u-Kult, 14.12.2010

On 7-9 October 2010, an international conference on ‘Plagues in Nomadic Contexts – Historical Impact, Medical Responses and Cultural Adaptations in Ancient to Medieval Eurasia’ was held in Leipzig. It was convened by Kurt Franz (Oriental Institute, University of Halle-Wittenberg) and Charlotte Schubert (Historical Seminar – Ancient History, University of Leipzig), on behalf of the Collaborative Research Centre (SFB 568) ‘Difference and Integration: Interaction between Nomadic and Settled Forms of Life in the Civilisations of the Old World’, and by Ortrun Riha, director of the Karl Sudhoff Institute for the History of Medicine and Sciences (University of Leipzig). It was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

The meeting aimed at integrating for the first time historical study of nomadism and the history of medicine. Epidemic disease has so far been examined almost exclusively in relation to settled societies and to agrarian economies. Now posed was the question: How and to what extent have epidemics affected societies involved in nomadic ways of life? Has the presence of nomads influenced the impact and perception of epidemics? A working hypothesis of the conference was that epidemics, and responses to them, have developed differently in societies in which nomads have had a distinct role.

Speakers were invited to address these issues with regard to the reconstruction of epidemics and their impacts; the endeavours of healers and physicians; and attempts to give social meaning to epidemics.

The conference began with greetings by the SFB’s vice-speaker, JÜRGEN PAUL (Halle). He accentuated as a major outcome of the research centre’s work that a fully nomadic group is a fictional type. Since ‘nomads’ regularly make use of the same resources, connections and interactions with settled people are normal. Epidemics transcend borders and different modes of life; they affect mobility and group responses in mixed societies.

Following Paul’s presentation, the opening address was given by the doyen of the medical history of classical antiquity, VIVIAN NUTTON (The Wellcome Trust Centre For The History Of Medicine at UCL, London). Largely denying the possibility of a retrospective diagnosis of epidemics and plague in particular, he focussed on what the explanations of epidemic tell us about society and culture. In ancient Greece, divine anger and mechanical causes like polluted air were the most widely accepted explanations. Individual responsibility was limited to individual illness. Unlike Latin antiquity (more so the Middle Ages) with its inclination to stigmatise extra-social agents, among them foreigners, Greek authors rated the Other low. Nomads were acknowledged in their capacities as wandering healers come with cures or healing music. Public civic religious action was conceived of as the most appropriate measure. Greek concepts show a society which was self-conscient enough to cope with epidemic within an extant cultural framework.

ORTRUN RIHA (University of Leipzig) introduced the Karl Sudhoff Institute, the founding place of the History of Medicine as a discipline. Section 1 then explored ‘Contagion and spaces.’ To provide a solid base, ARNE C. RODLOFF (University of Leipzig) outlined the microbiology of plague and its epidemiological impacts. He described the typical features of Yersinia pestis, its four biovars, and their contemporary geographic extension. The audience was struck by the facility of Yersinia pestis for genetic modification and of its potential as a lethal weapon. Recent progress in the detection of ancient plague DNA, it was pointed out, is now due to yield new historical insights.[1]

Historical debate was opened by RUTH I. MESERVE (Indiana University at Bloomington) who showed that the nomadic use of pastures in Central Eurasia has been closely tied to traditional shamanic folk medicine. It relates to geographic space and to the distribution of natural resources and disease areas. Mental maps show that infection paths are localised and boundaries and spatial markers are put up against the spread of disease, combining empiric and cosmologically defined spaces. Also, nomadic etiology in many cases infers disease from ‘dead land’ (körös ügei): pasture that has ‘lost its skin’ through building, farming, etc.

KURT FRANZ (University of Halle-Wittenberg) investigated the importance of steppes/deserts and their nomadic inhabitants for medieval Middle Eastern perspectives on plague. He argued that the traditional and theological Islamic stance that there is no contagion, but only divine will was contradicted by a number of medical authors and chroniclers who sought to substantiate the idea of infection through the medium of nomadic space and people: Dry wildernesses (tawahhush, etc.) were deemed salubrious places that prevented corruption of the air and body whereas contagious ‘poison’ would be endemic to many humid agricultural areas. This view drew on the literary image of the Bedouin as a savage accustomed to want and therefore robust.

With regard to eighteenth-century Ottoman Syria, YARON AYALON (University of Oklahoma at Norman) argued that while city-dwellers were more stricken by plague than mobile herders, economic interactions over time could level the differences. Nomads, for example, visited (sub)urban markets to sell lambs right when grain harvests were being transported and temperatures rising. This abetted an increase of rats and of infected rat-fleas in the towns’ outskirts. These held the more filthy crafts and also invited the temporary encampments of trading nomads now exposed to greater risks.

Section 2, on ‘Explanations and imaginations,’ examined the epistemic potential of nomads in relation to health and disease. This aspect was considered by every speaker of the conference, but it was a particular focus for the contributions on Greek antiquity, Byzantium, and Latin Europe which have not seen any sizable nomadic population. At the same time, perceptions of external nomads did influence the understanding of epidemics. CHARLOTTE SCHUBERT (University of Leipzig) pointed out that a most prominent nomadic figure, the legendary Anacharsis with his double Toxares, Skythians, attracted veneration by Greeks. Lukian presents their nomadic origin: the first as a sage, part of the tradition of the Seven Sages, and the latter as a healer. His kenotaph in Athens was visited by those ill with fever. At the time Skythian nomads were not unconditionally equated with Barbarians and could be appreciated for their skills. In Ionian geographical notions, they became a northern counterpart to the southern nomads of Libya, the region which served as the assumed origin point of epidemics.

Proceeding to Byzantine explanations of epidemics, KARL-HEINZ LEVEN (University of Erlangen) distinguished the ‘conventional’ explanations of theological authors from the ‘unconventional’ explanations of chroniclers. The first drew on classical literary models: miasmata, divine examination, and divine punishment (e.g., for migrating Barbarians who desecrated churches and saints’ graves), etc. The latter favoured a sceptical abstention. They stated the inexplicability of epidemic (e.g, when the people of Constantinople were struck and the mobile Huns spared), or personified plague as an actively wandering and even willful agens. Personification and demonisation became dominant patterns of explanation.

MICHAEL MEIER (University of Tübingen) commented on debates regarding the character and aftermath of the Justinianic Plague of 541/542, suggesting that its main impact was in the history of mentalities. General uncertainty, doubts of divine justice, and apprehensions about the end of time intensified a defeatism arisen from expectations of the end of the world in the year 500. On the other side, the cult of Mary, sacralisation, and liturgisation balanced this trend and ultimately triumphed, a mental shift of prime importance in the ending of antiquity and Christianity’s assumption of its medieval shape.

Following this, KLAUS BERGDOLT (University of Cologne) focused on the Black Death in Europe 1347-49 and the change of times it engendered. Looking at its impact on Italian society and culture, he postulated that the combined social, political, and economic crisis caused the end of the Middle Ages. The effects cut deeply into the history of mentalities.

At the beginning of section 3, ‘Livelihoods and mobility’, STUART J. BOSCH (Assumption College, Worcester, Mass.) drew a daring but revealing comparison between Egypt and England regarding the interdependencies of landholding structures and economic collapse or success, when challenged by a heavy population decline: The Mamluk system could not cope with that sharp drop and decayed. By contrast, English peasants benefitted from depopulation through individual bargaining and decreased rents.

ORTRUN RIHA (University of Leipzig) provided an introduction to medieval and early modern concepts of plague and outlined etiological concepts as well as the therapeutic approach. At the end, it was not medicine that met the challenge: In the case of an epidemic, public health policy was called for as exemplified by European plague treatises included in the Sudhoff Institute’s document collection.

Another view on mobility regarding Mamluk Egypt was presented by SARAH BÜSSOW-SCHMITZ (University of Halle-Wittenberg). Despite the traditional call for general immobility in the face of plague, reactions included flight from the towns but also to towns, apparently motivated by their relative wealth. Bedouins tended to avoid afflicted towns and individuals and often retreated to remote steppe but conomic interdependence and population densities in the zones of contact prevented isolation.

Continuing with Mamluk Egypt, BOAZ SHOSHAN (University of the Negev at Beer-Sheva) embarked on a historical reconstruction of the Black Death’s relative impact on peasants as opposed to Bedouins. A long term near-symbiotic coexistence, although interspersed with political tension, changed under the impact of demographic loss, agrarian havoc, and a decaying irrigation system into a downward spiral to the benefit of the Bedouins. Appropriation of agrarian lands and sometimes local political take-over were reinforced by tendencies towards desertification and a recession of cultivable land in the delta.

The final section 4 addressed large-scale circumstances and effects of the Black Death in Eurasia. In an attempt to explain the spread of the Black Death on the east-west axis, with the exception of China, PAUL D. BUELL (Charité, Berlin) suggested that while this spread may have been an indirect result of the Mongols’ move west and the intensified and accelerated exchange it created, there is little direct evidence associating the Mongols with plague. By contrast, the lack of relevant descriptions of disease from China during this period – the Golden Age of Chinese medical writing – was taken as proof that this region was spared despite a close association with nomadic peoples. Critical was the peculiar pathobiology of China and the fact that under the Mongols and during early Ming it was increasingly isolated from the overland Silk Road leading directly to Central Asian plague foci. The Indian Ocean, not effectively travelled by rats and fleas until modern times, had become the main channel of trade.

ULI SCHAMILOGLU (University of Madison at Wisconsin) then broached the hitherto untouched topic of how the nomadic-sedentary relationships in Western Eurasia underwent ethno-linguistic transformation in the 13th to 16th centuries and how this related to plague. He traced the collapse of centralised government, the abandonment of cities, and the rise of new nomadic confederations back to the Black Death.

The final discussion was initiated by two general responses. NICOLA DI COSMO (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, N.J.) distinguished the major strands of discussion: the difficult and challenging task of connecting local and trans-continental phenomena; the question of nomads as unintended facilitators of epidemics and their specific reactions to them; how to include concrete environments more or less favourable to nomads in the history of epidemics. JOSEF VAN ESS (University of Tübingen) noted that while the dawn of two new epochs in the Mediterranean and European region have been connected to epidemics, Middle Eastern history has not been so divided. Islamic doctrine saying that epidemic is a punishment for the non-believers and at the same time a martyrdom to the believer meant a leap into absurdity. Muslims have been badly equipped to respond to epidemics as forces transforming society, Van Ess argued.

The conference sought to overcome the concentrations of disciplines on single regional and cultural theatres, whether European, Middle Eastern, or Asian. Instead it has shown that epidemics and human reactions to them show comparable features, across disciplines:

The concept and discourse analysis is preeminent over attempts at retrospective diagnosis and epidemiology; local events and responses to epidemics are key and can affect supra-regional outcomes very differently; nomads have been ascribed a significant role in the course and aftermath of epidemics, and their behaviour, faced with epidemic, resembled that of sedentary people more often than not.

The nomadic context of epidemics has been shown to be substantial. ‘Plagues in nomadic contexts’ has thus offered a new way to connect the study of history, culture, and the history of medicine.

Footnote:

[1] A most recent aDNA analysis has now overcome long-standing dispute on the etiology of the European Black Death, proving that it was indeed caused by plague bacterium Yersinia pestis. See Stephanie Haensch et al., “Distinct Clones of Yersinia pestis Caused the Black Death,” PLoS Pathogens 6 (10): e1001134 <dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1001134> (01.12.2010).

Citation:

Conference Report Plagues in Nomadic Contexts – Historical Impact, Medical Responses and Cultural Adaptations in Ancient to Medieval Eurasia. 07.10.2010-09.10.2010, Leipzig, in: H-Soz-u-Kult, 14.12.2010, <http://hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/tagungsberichte/id=3431>.

© 2010 by H-Net and Clio-online, all rights reserved.